|

| I Made Wiradana: Raining #1, 130 x 150 cm Mixedmedia on canvas, 2012 |

One only has to listen to the dialogues between the members of Fighting Cocks Group Yogyakarta to see the passion for this theme, “And the Cocks Are Still Fighting,” and the eclectic selection of artists. As a group they are concerned with artists who have gone through a process of growth and found their identities whilst simultaneously being concerned with supporting new, lesser known artists. The members of Fighting Cocks Group Yogyakarta are Dedi Yuniarto as manager, Zam Kamil, Nurul ‘Acil’ Hayat, Moch Basori as the key artist members.AND THE COCKS are still fighting…!! Interpretations for this theme are broad although many of the artists reflect on the idea of struggle. The metaphor of a cock fight where the roosters inherently want to survive, pulling on a forces from all directions regardless of pain and imminent death, they still express a fighting spirit. For these artists, sometimes the opponent is themselves, sometimes the world of art and its “players”, sometimes just the reality of surviving and other times ideology -- ideology expressed by state, society and “isms”.

On the issues of “isms”, there are parallels between the era of Impressionism in Paris and the Paris of the Indonesian art world Yogyakarta. Yogyakarta is an artistically fertile community, thriving in its inspirations and its dialogues between artists that inhabit that community. Unprecedented at that time in Paris, was a visual literacy amongst artists and appreciators of all classes via the media and the reproduction of art. The world was expanding and travel had become easier, as it has now become for artists not only in Jogja but throughout Indonesia. Communication is quicker via the internet and artistic allegiances can be achieved in faraway places more easily. In Paris at that time, journalistic writing on art was also becoming popular and artists realised that they needed to court the media. Monet stated angrily in 1883, “Today nothing can be achieved without the press; even intelligent connoisseurs are sensitive to the least noise made by newspapers.”1

Consider the rise of art dealers deciding who sells and who does not, some of whom simply saw art as a business alongside those who were genuinely concerned about the wealth of artists. Patrons and collectors abounded acquiring paintings symbolising their wealth and providing financial sustenance for the artists, just as collectors do today often seeing art merely as investment. Artists in Indonesia are at a time where now, they are more visually literate than they have ever been before. Likewise, more than before, they are dependent on newspapers and curators to praise their work and of course, very dependent on patrons.

|

| I Made Wiradana: Raining #2, 130 x 150 cm Mixedmedia on canvas, 2012 |

The biggest difference between the artists of the Impressionist era and those now in Jogja is that there are few artists who come from aristocratic or bourgeois luxury. Many of these artists’s backgrounds are from peasantry, which in a society that values hierarchy places them in a very weak position to stand up for their rights. Like the artists of the Impressionists’s world, these Indonesian artists now seek to break away from dogma and define their world the way they see it 2.

One only has to listen to the dialogues between the members of Fighting Cocks Group Yogyakarta to see the passion for this theme, “And the Cocks Are Still Fighting,” and the eclectic selection of artists. As a group they are concerned with artists who have gone through a process of growth and found their identities whilst simultaneously being concerned with supporting new, lesser known artists. The members of Fighting Cocks Group Yogyakarta are Dedi Yuniarto as manager, Zam Kamil, Nurul ‘Acil’ Hayat, Moch Basori as the key artistic members.

For Fighting Cocks Group Yogyakarta, this selection of 18 artists was directed primarily by the desire to get back to the art and artists -- artist and the art as expressions of humanity and not just $ymbol$ of $ucce$$ and non-success; not just “important” artists because they have “NAMES”; nor labelled ones with titles such as “Emerging New”. This exhibition of Fighting Cocks negotiates senses of new, by moving away from the notions of important “players” in the world of Indonesian art. “New” here is not defined by what is created but our experience to it. They also value a sense of process and dedication regardless of how long someone has been a name in the world of Indonesian art. This is why you will find names like Dyan Anggraini and Nasirun alongside Ethel Kings and Untung Yuli Prastiawan who are relatively unknown.

This exhibition could be broken down into three broad categories and definitions of struggle or fight. The first is that of the artists’s personal struggle. The second would be the artists’s view of the world and struggles they have against the world and the transformations that occur in telling that story. And the third is the artists giving voice to others who are struggling. Beneath the surface, is also the story of the artists through these paintings and all have taken an understanding of the word “fight” or “struggle” in their works. These struggles take different forms; a struggle to hold true to ones artistic integrity in terms of the market, a struggle with oneself and ones responsibilities, a struggle to produce, a struggle with one’s own multiplicity of selves. There are artists who have the luxury of not caring what others think either due to financial freedom or lack of responsibilities to anyone other than oneself, whilst others have had to deal with demons tempting them to not change their style. Of course, each artist bears a perpetual questioning within. And the cocks are still fighting....

|

| Body Movement (diptych), 140 x 120 cm, Mixedmedia on canvas, 2011 |

|

| MAD, 200 x 200 cm, Acrylic on canvas, 2012 |

|

| Unfight, 55 x 75,5 cm, Mixedmedia on paper, 2012 |

|

| Gerak, 55 x 75,5 cm, Mixedmedia on paper, 2012 |

He sees the exhibition as focusing on the variety of choices one has in creative experience. For him, this is a joining of both his internal spiritual world and that of the physical world around him. He offers up two watercolours, “Unfight” and “Gerak” (Move). His free lines and vibrant colours are still apparent and yet “Unfight” voices the battle of the more peaceful colours of the spectrum to ascertain calm over the more fiery elements of the oranges and yellows. Like many of the paintings in this exhibition, there is a symbolic hand reaching up expressing a yearning. In “Gerak”, a landscape of greys features a lone figure not dissimilar to Suharmanto’s becak driver in “Tuhan Sedang Melihat” (God is Watching). These figures which seem to be so distant affect a sense of timelessness towards the concept of individual struggle.

In “Tuhan Sedang Melihat” (God is Watching), Suharmanto gives voice to the rakyat jelata (common people) by taking a bird’s eye view of a becak driver. Suharmanto still has elements of his trademark style of painting in dynamic, hyper-realistic colours with a masterful playing of light on reflected surfaces. In contrast to Gusti Alit Cakra’s very full canvass of many struggling and Basori’s large face expressing heroism, Suharmanto’s protagonist is physically small in the scheme of things.

|

| Tuhan Sedang Melihat, 180 x 150 cm, Acrylic on canvas, 2012 |

Like Suharmanto, Ethel Kings’s “Fight for The Light” contrasts with Sufriadi’s and Budhiana’s very free work (and influences by such Western artists as Jackson Pollok and Basquiat), Ethel Kings seems to be painting in a very fixed style. Unlike the three artists above, she has no formal art training or knowledge of art history in Indonesia. She is an Estonian who has been living in Indonesia for one and a half years and ironically her work seems to reflect the process of acculturation that she is unwittingly going through -- the process of adopting the other to find oneself.

|

| Fight for The Light, 150 x 130 cm, Oil on canvas, 2012 |

Similarly, a stream of consciousness through cultures, multiple selves, time and space dance across the canvas in “Auver Someday, Somebody, Vincent and Me” by Zam Kamil. Zam Kamil is an artist from Makassar domiciled in Jogja. He is overwhelmed by two contrasting mythologies that of Vincent Van Gogh and I La Galigo. Taken together, Van Gog’s tormented like in art and Sulawesi’s epic poem I La Galigo are married in the work of Kamil. The culture of Sulawesi divides human beings into four genders, male, female, female form male soul, male form and female soul.

|

| Auver Someday, Somebody, Vincent and Me, 200 x 300 cm, Oil on canvas, 2012 |

The myth of Sisyphus and his perpetual struggle of pushing the rock up the hill only to roll back down again; the absurdity of life which is teeming with a load of problem; and an arc that carries the hopes and dreams of civilisation or simply a boat that carries the dead; Budi 'Bodhonk' Prakoso‘s “Melewati Batas-batas” (Overcoming Limitations) is another that is steeped rich in symbolism of the struggles of common people. His little people float through the grey of their lives, boxed in, struggling to achieve their dreams. The soul of the artist is etched into the body of a character who is not carried away into a sea of dreams but carries the boat. His history and feelings are written up in his very flesh. Civilizations are built on desire for change and the hope of a safe house and yet the reality is that in this process, as with the great pyramids, hundreds even thousands little slaves fall unwittingly to their deaths without ever achieving the first level of their hopes.

|

| Melewati Batas-batas, 150 x 200 cm, Acrylic on canvas, 2012 |

Acil’s “Single Fighter”, also personalizes struggle and gives voice to the ‘rakyat jelata’ in the sculpture of a rice farmer, half falling, struggling to stand with a distorted body.

|

| Single Fighter (model to aluminium) 70 x 60 x 85 cm, Newsprint, 2011 |

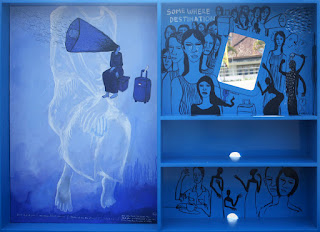

Daniel Rudi Haryanto’s installation and video art, “Marline and The Blue Channel” gives voice to the struggles of single TKW (migrant worker) whose story is similar to the many who have chosen to work overseas to get out of cycle of poverty and who often face abuse from employers in the countries they work in and are not supported by their own country.

|

| Marline and The Blue Channel, 100 x 120 x 20 cm, Multimedia: wood, audio visual, 2012 |

|

| Fighting Series #3, 100 x 125 cm, Burning technique and oil on canvas, 2012 |

|

Nginang Karo Ngilo, 180 x 150 cm, Mixedmedia

on canvas, 2012 |

Rocka Radipa plays with two faces, two sides of the same blade and two meanings of a word in “Backsword Eternal”. The decorative, hook like knife, is essentially useless but still potentially dangerous. It is decorated in with “pamor”. Pamor is a decoration etched into traditional Indonesian’s kris 7 which sometimes imbue the kris either through its design or words with mystical powers. The word pamor in Indonesian also means lustre or prestige. The word war reflects as peace and the question is whether peace is guarded so there can be no more war or whether war is fought against evil in the search of peace?

|

| Backsword Eternal, 250 x 80 cm, Brass etching mixedmedia, 2012 |

|

| Potret Negeri Hiruk Pikuk, 250 x 180 cm, Mixedmedia on canvas, 2012 |

Nasirun, an artist who needs little or no introduction, has achieved what Van Gogh never achieved in his lifetime a position of importance in both the Indonesian and international art world and financial security. Despite this he has never forgotten his roots and approaches his work by digging deep into his cultural and filial history.

+Imajinasi+Dasamuka+145+x+89,5+cm,+Oil+on+canvas,+2009.jpg) |

| Imaji Dasa Muka, 145 x 89,5 cm Oil on canvas, 2009 |

Tri Suharyanto’s sculpture, “Ideologi”, presents his desire to talk about Indonesia today. However, Tri has fallen prey to the dogma of patriotism with his desire to speak passionately about the power that Pancasila could be. Ironically, his statue seems to speak inherently of what his soul already knows. Unlike Nasirun’s and Acil’s work, where the body is clearly Asian, Tri’s body is that of body builder, an obsession with perfection that looks good but is not functional -- it is also this obsession with human perfection that contributed the notions of the Aryan super race and later the extreme notions of nationalism that led to the Holocaust.

|

| Ideologi, 186 x 146 x 46 cm, Resin polyester, duco color, mixedmedia, 2012 |

Moch Basori’s latest work, “Podojoyonyo”, like Nasirun’s work, draws on traditional folklore. The expansion of the hero’s face also has that sense of being outstretched in its power like Tri’s symbol of the Garuda. The slashing brush strokes seem to cut into the face deeming the protagonist fresh from battle. The ambiguous smile of one who sees himself as the hero despite being responsible for the chaos through poor leadership 10. The expanse of the face across the canvas and the bright colours, the spirit of the fighter captured in the eyes of the protagonist, contrasts with Tri’s. Both are legends. One as a mythical hero of Javanese folklore and the other (both the artist and the art player) in the world of Indonesian art moving towards folklore. What is striking is that Tri’s reminiscence of the power of Indonesia in the past and Basori’s reminiscence of a mystical heroic figure reflect nationalism, yet ironically neither of these two artists transfer that heroism to bodies that are typically Indonesian.

|

| Podojoyonyo, 150 x 200 cm, Mixedmedia on canvas, 2012 |

In contrast to Tri’s bombastic symbol of perfectionism, Basori’s figure of heroism and Ivan’s slightly more blatant commentary, Dyan Anggraini’s “Still Surviving” shows the power of the Asian body -- the proud and beautiful posture, elegant yet strong arms and hands. Anggraini’s character is still but not stiff, a relaxed state that is potent with power. Like Nasirun, she draws on elements of tradition in her use of Topeng.

|

| Still Surviving, 150 x 150 cm, Oil on canvas, 2012 |

And so it can be said, Dyan Anggraini’s protagonist reflects the souls and the spirit of these artists, principled and defiant regardless of what the players of Indonesian art say. In the text in the Sulawesian language of Zam Kamil’s painting: sellu’ka riale kabo, fusa, nawa-nawa, naiyya ati, mallolongeng (i am lost in a wild jungle, my thoughts are lost and yet my heart find them). The artists find themselves in their defiance. Regardless of the individual hardships they face -- the financial struggles, artistic warfare, treachery and accusations -- the cocks are still fighting.

Bandung, May 2012

Kerensa Johnston

Footnote:

1 Pg. 13 Denvir B., The Chronicle of Impressionism, Theames and Hudson, 2000, London.

2 Denvir, B.,The Chronicle of Impressionism, Theames and Hudson, 2000, London.

3 Kecak is the monkey dance of Bali where a chorus of men often with raised hands chant ‘cak-cak-cak’.

4 Megamendung is a cloud motif found in the batik of West Java.

5 “Looking at mirror, whilst chewing tobacco”.

6 Pg. 190 Suardika I.W. Crossing the Horison, Matamera Books 2010, Denpasar.

7 Kris is a ceremonial, double-edged wavy blade found in Bali and Java. Many kris are passed down through families and are said to have mystical powers.

8 “Portrait of Noisy Land”

9 Pancasila is the state ideology of Indonesia. There are five elements: 1. A belief in one God; 2. A just and civilized society; 3. The unity of Indonesia; 4. Democracy guided by the inner wisdom via process of deliberations amongst electives; 5. Social justice for all Indonesians.

10 The story is a folktale of a King who gave instructions to one of his followers not to let anyone to look after his kris and not give it to anyone else but himself. The King then gave instructions to another follower to go and get the kris. Both fought with passion because their promise to the King and the instructions they gave him. The story also symbolizes the start of the Javanese alphabet. The meaning of the phrase is ‘Both are equally strong, both are equally glorious’.

No comments:

Post a Comment